It has become fashionable in some circles to refer to Mary as “the mother of Jesus” rather than the more traditional appellation “Mary, mother of God”. The aim of such a change is clear; it was to diminish the strength of the connection of Mary to God. Mary, as it is reasoned, is human, therefore it is proper to emphasize her human connection to God as a human: Jesus. Unfortunately, this harkens back to an old heresy: Nestorianism. This heresy denies Mary carried God in her womb. Rather, it asserts that Mary only carried Christ’s human nature; however, the Church rightly teaches that Mary carried the whole person of Jesus in her womb, not simply a “nature”. This teaching was affirmed at the Ecumenical Council of Ephesus which countered the Nestorian heresy: “According to this understanding of the unconfused union, we confess the holy Virgin to be the Mother of God because God the Word took flesh and became man and from his very conception united to himself the temple he took from her" (Formula of Union [A.D. 431]).

Why is this teaching so important? Because it tells us something essential not only about Mary but about how “for God, nothing is impossible”.

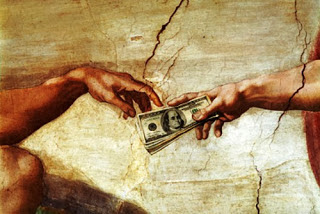

As Mother of God, Mary carries Jesus as the second person of the Trinity to present Him to the world. God did not choose to manifest Himself as human fully formed, but chose to enter the world through His own creation; He was not created anew but submitted to being born a human that we might find a way to divinity. As St. Paul writes in his letter to the Philippians:

5In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus:

did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage;

7rather, he made himself nothing

by taking the very natureb of a servant,

being made in human likeness.

8And being found in appearance as a man,

he humbled himself

by becoming obedient to death—

even death on a cross!

9Therefore God exalted him to the highest place

and gave him the name that is above every name,

10that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow,

in heaven and on earth and under the earth,

11and every tongue acknowledge that Jesus Christ is Lord,

to the glory of God the Father

Mary’s participation in “The Great Condescension” of God, suggests a way of being in relationship with God, a spirituality par excellence if you will. Mary’s role is to lead us more perfectly to Christ, and Christ’s role is to unite us to God. What are these “leads” Mary provides?

Firstly, she became vulnerable to God’s will. She proclaims "I am the Lord's servant. May everything you have said about me come true." She not only did the will of God, she willed the will of God. This is every Christian’s goal. Uniting to God’s will requires allowing God to work in us, even in the times we are least sure and most afraid. Like Mary who could not fully comprehend how this would turn out, her great faith in God’s goodness gave her the power to participate in humanity’s salvation.

Secondly, Mary’s role was not passive. Very often Mary is presented as singularly inactive. Luke 2:19’s famous observation of Mary “pondering these things in her heart” in response to the unfolding of God’s plan as the shepherds told their tale is not a passive participation, a “wait and see” approach. Submitting one’s life to Christ is anything but passive. Mary’s “pondering”, in Greek “sunballousa” suggests the activity of gathering and comparing. Luke’s famous “Song of Mary” in 1:26 suggests Mary’s joy and sense of mission that extends to us today:

His mercy extends to those who fear him,

from generation to generation.

51 He has performed mighty deeds with his arm;

he has scattered those who are proud in their inmost thoughts.

52 He has brought down rulers from their thrones

but has lifted up the humble.

53 He has filled the hungry with good things

but has sent the rich away empty.

from generation to generation.

51 He has performed mighty deeds with his arm;

he has scattered those who are proud in their inmost thoughts.

52 He has brought down rulers from their thrones

but has lifted up the humble.

53 He has filled the hungry with good things

but has sent the rich away empty.

Mary’s gift to us is not only Christ but also the wisdom of a life so intimately associated with God’s plan for humanity’s salvation. It is a spirituality of humility but not inaction, it is a spirituality of “pondering” and response. In short, Mary’s life offers us a life of complete wholeness as we allow the Spirit to work in us. Meister Eckhart said it best: We are all meant to be mothers of God, for God is always needing to be born.